5 Reasons Every Lawyer Should Study the Art of Screenwriting — and a Killer Resource List To Get You Started

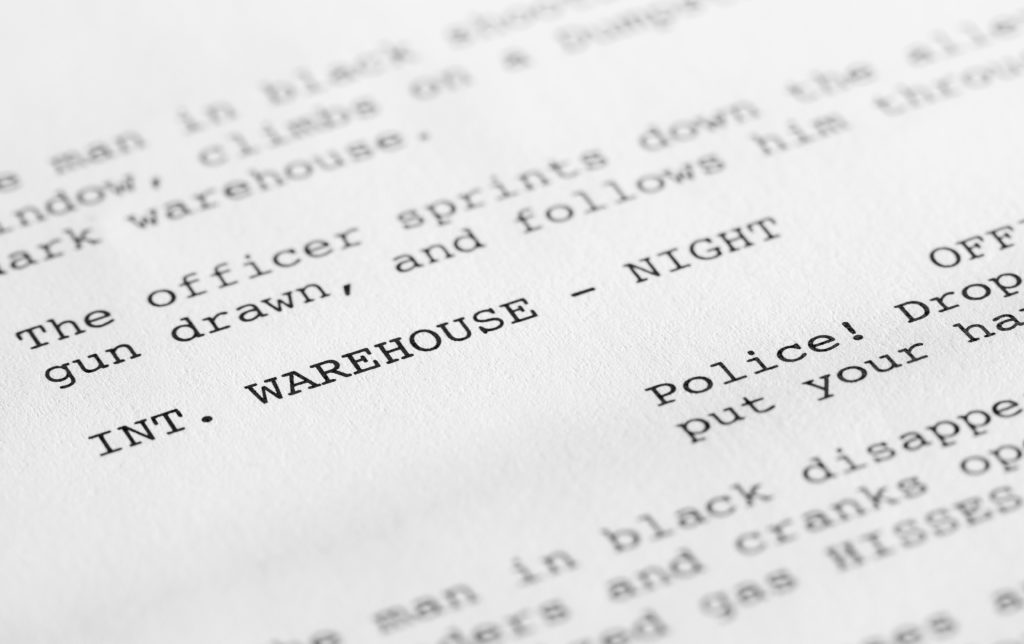

So, you love watching movies — but have you ever read a screenplay? You would be amazed at just how descriptive, precise, and emotionally compelling this very distinct form of writing can be. Before I lay out my list of favorite screenwriting resources, here are five reasons why peeling back the layers of technique behind the art and craft of screenwriting is guaranteed to make you a better storyteller, a better writer, and a better lawyer!

So, you love watching movies — but have you ever read a screenplay? You would be amazed at just how descriptive, precise, and emotionally compelling this very distinct form of writing can be. Before I lay out my list of favorite screenwriting resources, here are five reasons why peeling back the layers of technique behind the art and craft of screenwriting is guaranteed to make you a better storyteller, a better writer, and a better lawyer!

1. Studying screenwriting will unlock the DNA of story and set you on the path to becoming a master storyteller.

Scripts and books about writing them are step-by-step guides to story construction. They teach us about plot and subplot, conflict, obstacles, reversals, rising tension, and resolution. These resources show you how to infuse your stories with deeper meaning and reveal the universal truths your stories reaffirm. There is no better way to learn the subtle craft of forging empathetic connections with characters who may have done bad things or may be, to put it charitably, less than likable. In those pages you will learn how to hook, hold and take your audience on a journey that inevitably lands them safe and sound at the exact place you need them to be.

2. Learning screenwriting teaches you how to come out swinging.

A person writing a script is trying to sell a script. In order to do that, he must wow the reader on page one. Beyond that, the first ten pages are crucial to keep the reader engaged until he reaches the point where he is committed to seeing how the story will end. If the reader loses interest before he gets through the first ten minutes – he’s done.

Isn’t this the same with our own written work? Are we wasting the first precious pages of our briefs droning on with boiler plate legal mumbo jumbo that the judge has read and heard a million times? If so, that probably means your reader is skimming, or worse, skipping pages trying to fast-forward to the “good part” that probably isn’t even there. That is no way to fire up a reader and get them on board with your cause.

Take a look at any great screenplay, and watch how the writer “has you at hello”.

In honor of the recently departed John Hurt, here’s an example — page one of The Elephant Man, written by Ashley Montagu:

BLACK

FADE IN: ABSTRACT DREAM

CLOSE-UP of a gold framed miniature portrait of JOHN MERRICK’S MOTHER (tune or melody over her picture, heartbeat), which DISSOLVES TO CLOSE-UP of real Mother smiling

– a shadow comes over her face – CLOSE-UP of elephant ears, trunks, faces moving.

Dark, heavy feet stomping – elephant trumpet – rearing up.

Powerful hit and the Mother falls – darker – trunk slides over Mother’s face and breasts and stomach, leaving a moist trail.

MOTHER’S POV of elephant’s mouth, eyes, skin – Mother’s face twists and freezes in a blurred snap roll.

BLACK again – knock, knock sound – curtain opens to horrified faces.

CUT TO BLACK AND SILENCE

CIRCUS

FADE IN TO steam shooting out of a huge old half-rusted calliope. The music is very loud and raucous. Moving up and back we see the black awning entrance to the freak tent, where FREDERICK TREVES, Resident Surgeon and Lecturer on anatomy at the London Hospital, is standing with his back to us observing the posters of the freaks.

3. Learning screenwriting will teach you how you write concisely.

Judges and juries are waiting for a good true story, but they aren’t looking for the Great American Novel. We lawyers tend to love our words. Long sentences. Lots of commas. Run-ons. It’s cheaper than Ambien, but it doesn’t win the day.

In screenwriting, because one page of a script equals one minute of movie time, a screenwriter has to cram the whole glorious story into 90-100 pages. That means good screenwriters know what good lawyers need to know: “every single page, paragraph, sentence, and word in your script is important.” See Karl Iglesias, Writing For Emotional Impact 61-76 (WingSpan Press 2005). For example, Iglesias shows us how some top-of-their-game screenwriters reveal the essence of their characters with an astounding economy of words:

WARDEN SAMUEL NORTON strolls forth, a colorless man in a gray suit and a church pin in his lapel. He looks like he could piss ice water.

-Frank Darabont, Shawshank Redemption

DARRYL comes trotting down the stairs. Polyester was made for this man, and he’s dripping in “men’s” jewelry.

-Callie Khouri, Thelma & Louise

This is RICKY FITTS. He’s eighteen, but his eyes are much older. Underneath his Zen-like tranquility lurks something wounded… and dangerous.

-Alan Ball, American Beauty

4. Screenwriting resources teach the value of painting “Word Pictures”.

A movie is a story told in pictures. Syd Field, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting 41 (Dell 1994). The masterful screenwriter knows his writing must allow the reader to see the movie in his mind. He doesn’t use bland, conclusory language such as, “The large man was intoxicated and threatening”. Instead, he says, “He was six-two, six sheets to the wind, rage oozing from every pore.” His language is ever expressive. He doesn’t use big words for the sake of showing how erudite he may be. Painting word pictures will keep the reader on the edge of his seat, eager to turn to the next page.

Here’s a deliciously disgusting example (also from Iglesias’s Writing for Emotional Impact) of vivid, visceral writing:

A red stain.

Then a smear of blood blossoms on his chest.

The fabric of his shirt rips apart.

A small head the size of a man’s fist pushes out.

The crew shouts in panic.

Leaps back from the table.

The cat spits, bolts away.

The tiny head lunges forward.

Comes spurting out of Kane’s chest trailing a thick body.

Splatters fluids and blood in its wake.

Lands in the middle of the dishes and food.

Wriggles away while the crew scatters.

Then the alien being disappears from sight.

Kane lies slumped in his chair.

Very dead.

A huge hole in his chest.

–Alien, by Walter Hill & David Giler

Imagine if you could weave together a visual tapestry of story in the same way during your closing argument? You would have a jury eating out of the palm of your hand.

5. This s*&t is FUN!

Our job is not easy. It is no coincidence that lawyers have the highest rates of addiction and suicide of any profession. How cool is it that we have the ability, dare I say the mandate, to immerse ourselves in story craft and chalk it all up to professional development? So, be kind to yourself. Log off of Westlaw. Put that appellate brief you’ve been slaving over on pause until tomorrow. Pour yourself (a moderate sized) glass of your favorite beverage– and dig into a good book on screenwriting!

RESOURCE LIST:

Here are my favorite books on screenwriting and story craft, with links to Amazon.com in case you are ready to take the plunge:

1) Story: Substance, Structure Style and the Principles of Screenwriting, by Robert McKee

2) Writing for Emotional Impact by Karl Iglesias

3) The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 3rd Ed. By Christopher Vogler

4) Essentials of Screenwriting: The Art, Craft, and Business of Film & Television, by Richard Walter

FREE SCREENPLAYS!

There are many resources online for FREE screenplays. I am always a little wary of “free” stuff, because you never know what that click is going to do. That said, I have downloaded from both of these sites without any apparent issues:

Finally, in honor of Oscar season, here is a link for free downloads of 9 of the 10 screenplays nominated for the 2017 Oscars:

http://nofilmschool.com/2017/01/download-x-10-screenplays-nominated-2017-oscars-right-now

Enjoy!